We interviewed Professor Jiro Yasuda of the Institute for Tropical Medicine, who is working as an expert on the Project for Establishment of Laboratory Surveillance System for Viral Diseases of Public Health Concern, an ongoing project in Gabon since 2016, about the project initiatives and current state of affairs.

―― Although infectious diseases account for half of all deaths in Gabon (WHO, 2011), we have heard that the country’s capacity to deal with emerging and reemerging infectious diseases is low, and even core research institutions have little experience in this area.

This project aims to improve Gabon’s capacity for research and development on viral infections by conducting joint research with the Medical Research Center of Lambarene on the development of rapid diagnostic methods for viral infections with a high priority in terms of public health.

How did you come to be involved with infectious diseases and what led you to join this project as an expert?

Prof. Yasuda: Originally, I was conducting molecular biological research on viral hemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola, Marburg disease, and Lassa fever, which are highly pathogenic viruses with extremely high mortality rates and are classified as Class 1 infectious diseases in Japan. There was talk about creating a new laboratory and a viral research center at Nagasaki University, and I was invited by then-President Katamine to join this effort, so in 2010, I transferred to the Institute of Tropical Medicine. You cannot get the full picture of infectious diseases in a lab; you can learn many things by going to the places where these diseases are occurring. I had just transferred to the Institute of Tropical Medicine and wanted to do field work as well, so the first disease I tackled was Lassa fever in Nigeria because I knew some international students from the country. Later, in 2015, the Ebola pandemic struck West Africa. Since I had initially conducted research on Ebola and had developed a diagnostic method for the disease, I decided to conduct actual evaluation tests in the field of the method I had previously developed. I did these tests in Guinea because of my ties with an Assistant Professor from Guinea. I also assisted with work on the Zika virus in Brazil.

Prof. Yasuda: There have been four Ebola outbreaks in Gabon since around 2000. Because my background is in veterinary medicine, I was very interested in how this disease was affecting wild animals. Forest accounts for 80% of the land area in Gabon, and there are many protected species of wild animal there, including the Western lowland gorilla. Unfortunately, about 5,000 gorillas died from Ebola. I was interested in zoonotic diseases and thought that I could do something in Gabon, so I joined the project. Infectious diseases spread across national borders, so I was also interested in the various viral infections in the neighboring countries around Gabon. The idea of cooperating with Gabon was raised within the Institute, so I applied for the project with the support of the Japanese Embassy in Gabon and was fortunate enough to be selected.

―― Can you describe the progress and outcomes of the project so far?

Prof. Yasuda: We conducted a preliminary survey in 2015 and started the project in 2016, so it is now in its fifth year. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we could hardly conduct any activities in FY2020, so the project period ended up being extended. With the resumption of air travel, we are gradually moving ahead with project activities.

Prof. Yasuda: It’s been five years, but we had a lot of trouble at first, mainly with communication. We had to start from scratch since Gabon was a country where we didn’t have any existing connections. We started by collecting samples, but at the launch of the project with the Medical Research Center of Lambarene, we did not even know what viral infections were prevalent in Gabon each year. We have to figure out which viral infections are causing problems. After that, we will introduce a system to enable the diagnosis of those viral infections in the field. This is the path we are taking.

Prof. Yasuda: I’ve come to realize several things working on this project. For example, there are four serotypes of dengue fever, and it used to be thought that Type 2 was the main type, but we have found out that this has actually been shifting to Type 3 over the past five years. We are also starting to understand the infection routes of hepatitis viruses, which is something that was not widely reported on in the past. In many ways, we are beginning to understand the real situation on the ground.

――In your research thus far, what has brought you joy and where are you still dissatisfied?

Prof. Yasuda: I am definitely not satisfied. (haha) But I don’t think I ever will be. As I say to the young people, we haven’t accomplished anything yet. That’s why we need to work more diligently on various things. I’ve been doing this for 30 years, but I don’t think even I have accomplished anything yet. I’m trying to figure out what I can do over the next 10 years.

Prof. Yasuda: There are many small things that have made me happy. For example, when we went to Guinea, the local children would gather around us and touch us. They would hold our hands because Japanese people are rare there. People are always happy when they are welcomed with open arms. Also, doing this kind of work allows me to go to many places. The place where we are working in Gabon is 270 kilometers away from the capital city. I get to go to places where we have to drive for four or five hours on unpaved roads, and I can interact with many different people and cultures. I am not so much as happy, as I am having fun.

Prof. Yasuda: Having fun is important. The most exciting thing about research is making the unknown known. By making discoveries, we can change the unknown into the known. This is what makes the work interesting and fun.

Prof. Yasuda: Our hope is that people will read these interviews and say, “I would like to do field work in Africa,” or “I would like to do virus research.” For us, that would be the most exciting response we could receive.

――You mentioned the advantages of fieldwork, but have you ever felt fear in a situation where, for example, there is a gorilla lying on the road and it might be infected with a virus other than Ebola that is unknown?

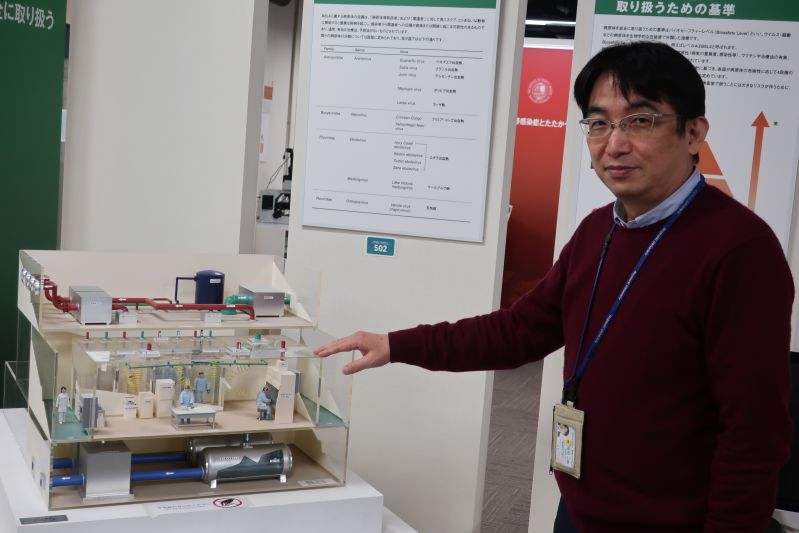

Prof. Yasuda: No! (haha) Graduate students and international students often ask me this question: Why are you researching Ebola in a region as dangerous as Lassa when there are no such high-risk pathogens in Japan? We are experts, so we know how to protect ourselves. There is a risk of accidental injury, like a sick person grabbing on to us or someone shooting at us. However, for most comes to infectious diseases, if you properly wear a mask, double gloves, protective clothing, and face guards to protect your eyes, you will not contract the disease. If you know how to avoid infection, then it is not so dangerous to handle pathogens.

――What are your future plans in Gabon?

Prof. Yasuda: I would like to continue this research for five more years. If we can do that, we can develop a more detailed understanding of infectious diseases in the country. If our pilot study goes well in Gabon, it will be possible to deploy our diagnostic system in neighboring countries.

Prof. Yasuda: I also hope that we can feed the outcomes of our research back into society by collaborating with the private sector, for example, by introducing diagnostic methods to local communities, developing drugs that will be useful in combating infectious diseases, and in terms of pure science, discovering new knowledge about viral infections. In terms of collaboration with the private sector, Canon Medical’s rapid virus detection system, whose development we were involved in, has been adopted by JICA as one of its public-private partnership projects (“Business Model Formulation Survey for Rapid Virus Detection System in Gabon”), and we hope to introduce a system that meets the needs of Gabon.

Prof. Yasuda: I mentioned zoonotic diseases earlier, but we are also collecting specimens from wild animals in the project, and we have found various viruses in those specimens. We believe that some of these viruses may be the pathogens that may cause the next new infectious disease, so we would like to find viruses like these and their genes so that we can determine what infectious diseases might become a public health problem for humans next. There are so many things I want to do. Infectious diseases do not have national or regional boundaries, nor are they limited to a single animal species. Viruses are global. If the entire global environment is not healthy, people cannot be healthy either.

―― In conclusion, what do you find most appealing about Nagasaki University?

Prof. Yasuda: When I was young, I switched laboratories after three or four years, but the most important thing for a researcher is the research environment and whether or not he or she can do the research he or she wants to do. I came to Nagasaki because I wanted to do the research that I wanted to do, and fortunately, I was blessed with good timing and a wide array of contacts. The reason I have been at the Institute for 10 years is because of the good environment. It is a top-level research environment. Another good thing about the Institute is its networks. There are graduates all over the world, and they create networks in their own countries. When I said I would go to Guinea, I was able to contact some of them through the alumni network.

――Thank you very much for talking with us today.

Professor Jiro Yasuda